3/19/07 Rising Up On The Hill by Mindy Farabee

Rising Up on the Hill

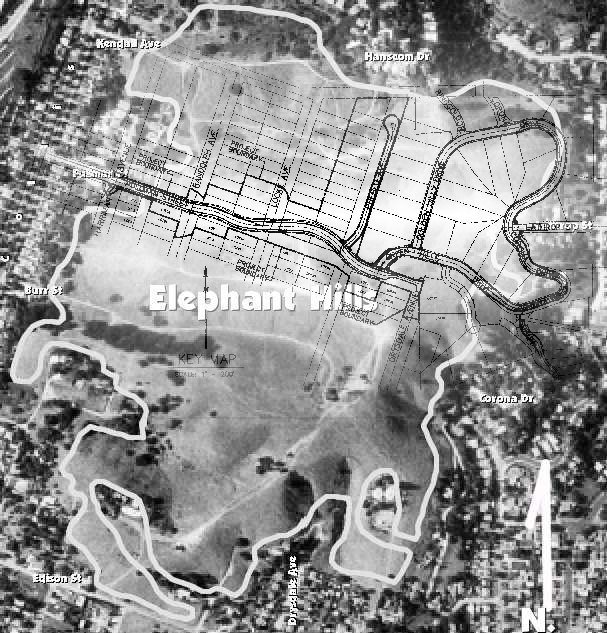

El Sereno residents desperate for parks hope to save Elephant Hill from development

~ By MINDY FARABEE ~

Los Angeles City Beat, December 7, 2006

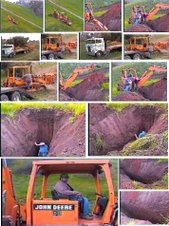

lva Yañez offers up a color printout, a sort of people’s Exhibit A, showing a John Deere bulldozer

up to its elbows in a muddy sinkhole. "It would be nice to preserve our hillsides as a place for the community

to recreate, but first things first – let’s make sure this development doesn’t end up with situations like this," she

says. Alongside the dozer, Yañez, executive director of the Audubon Center at Debs Park in Highland Park,

has placed another picture, this one of a single family home situated just downstream from the first, sandbags

holding back the swampy mess.

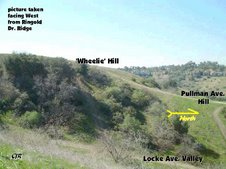

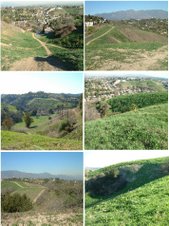

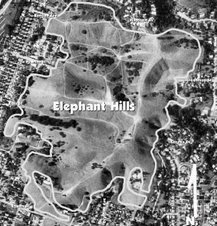

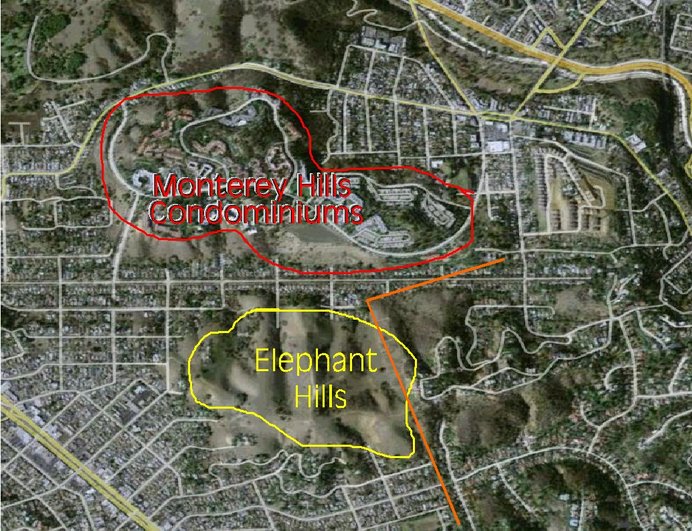

Taken this past April, just days after work began on access roads for a new 24-home subdivision on Elephant

Hill, a loping 110-acre parcel of open hillside in the Northeast Los Angeles neighborhood of El Sereno, the

photos are a disaster – but also could be a harbinger of better things to come. Residents say they prove

environmental reports used to approve the development are seriously flawed. And now, after fighting the city’s

planning department for more than a decade, these squeaky wheels have finally started the gears of

bureaucracy turning in their direction.

There is a precedent for concern in these neighborhoods. Back in the 1980s, millions of dollars in lawsuits

exploded across the nearby community of Monterey Hills as homeowners sued everyone they could get their

hands on, including various city entities, for constructing their condos on unstable ground. Now Yañez and

others fear this new project is setting everyone up for a repeat.

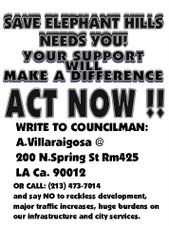

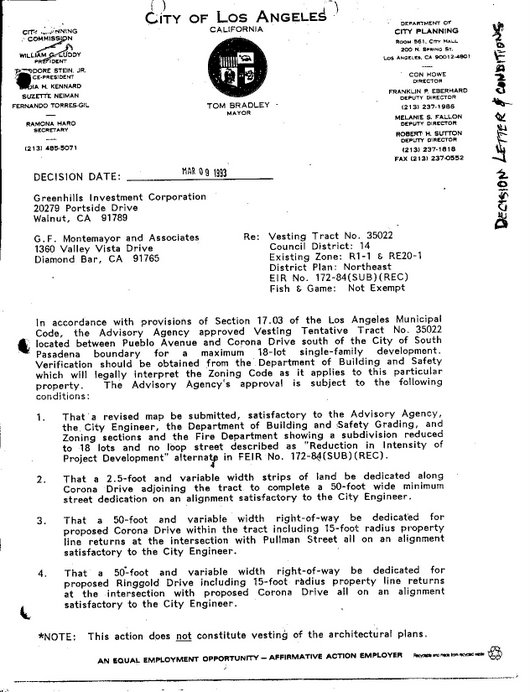

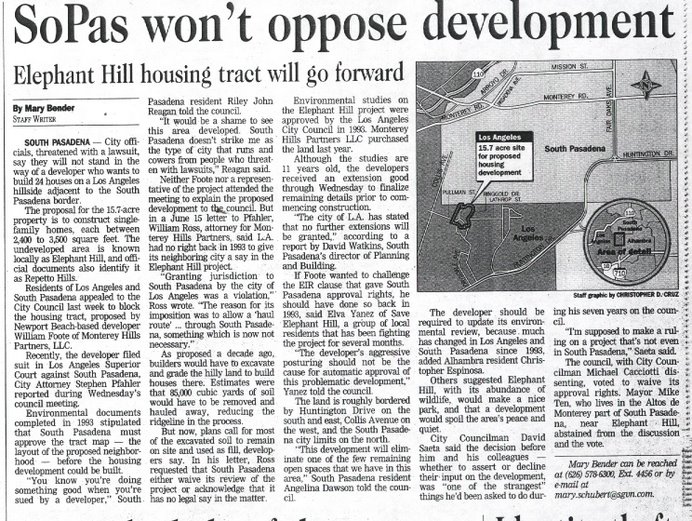

Yañez’s new nemesis is actually an old subdivision, an early ’90s proposal opposed by the community since its

inception. Approved by the city despite vocal resistance, residents were originally saved at the 11th hour by a

real estate bust that halted construction across the Southland. In 2003, however, a booming market

reinvigorated the idea, and Yañez, who lives on a quiet cul-de-sac at the hill’s base, helped lead an impressive

counterattack. Petitions were signed, electeds were lobbied, and once it was put on the agenda, over 200

protestors showed up at a neighborhood council meeting, an unprecedented number for East L.A. The city’s

two eastside council members, the region’s two state Assembly members, and even the mayor of adjoining

South Pasadena all joined in to fight the development.

Then the developer sued the city and the city caved. "Even just going over this makes me very sad," Yañez

sighs.

"The community was devastated. People said, ‘See, we get screwed all the time, it doesn’t matter what we

do.’"

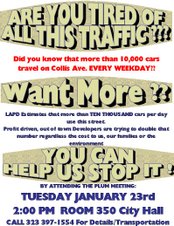

For years, those residents say, their neighborhood was the backwater of the backwater, an overlooked corner of

overlooked East L.A. "Maybe it’s because we’re at the northernmost and easternmost edge of the city,"

speculates Hugo Garcia, president of the local neighborhood council. Garcia’s family moved to El Sereno in

the early 1960s, and over the past 40-plus years he’s watched a jumble of boxy apartment buildings and

escalating cut-thru traffic clutter up his neighborhood. "In El Sereno, we’ve been neglected and taken for

granted and run roughshod over. When it comes to business development plans, or resource allocation, or a

plan to preserve open space, we don’t get it."

It seems odd to hear Yañez give her neighborhood kudos for being a safe place for kids to play in the street –

until learning that Northeast L.A. has one of the lowest parkland-to-people ratios in Los Angeles. Here, official

open space clocks in at under two acres per 1,000 people, and just getting to the largest ones can be a

complicated and kid-unfriendly experience in this congested, freeway-infested region where many residents

commit the unheard-of sin of not owning an automobile.

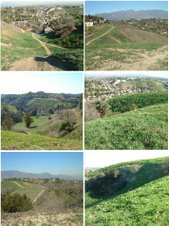

The majority of the vacant lands remaining in Northeast L.A. – of which Elephant Hill is one of the largest –

are privately owned. With limited access to municipally sanctioned parks, the community long ago co-opted

these hillsides. "People were hiking in it, and taking dirt bikes up there, and just hanging out," Garcia says.

"We have a significant indigenous population here and an Indian friend of mine goes up there to collect wild

sage. [With this development] we lose our ambiance, our open space, and what do we get out of it?"

Garcia says it didn’t take long for his neighbors to figure out the luxury homes planned for Elephant Hill,

tentatively priced around $750,000, weren’t designed to house El Sereno’s mostly working class residents, but

what really concerns them is "the potential for future development," he says. "It looks like it’s going to

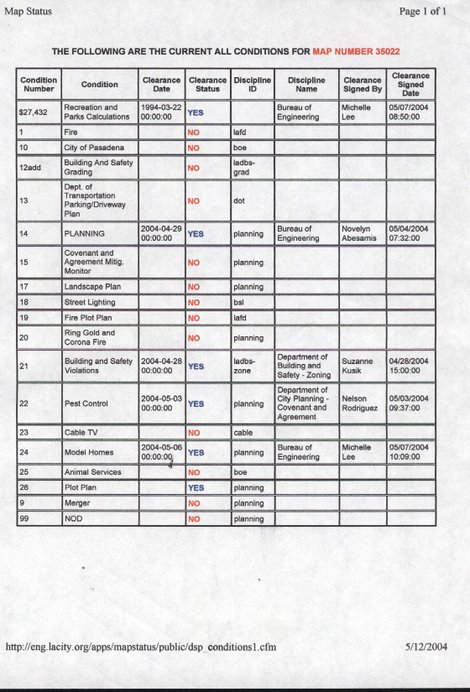

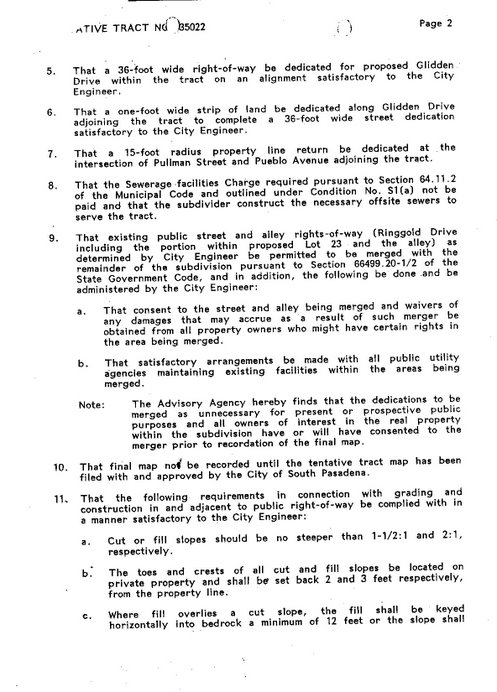

snowball." New paperwork filed with the city seems to indicate that the project is piecemeal and has expanded

from even the 2004 version.

Under California’s Environmental Quality Act, that may be illegal, one of many facts mentioned among the

flurry of one-sided correspondence generated on the community’s behalf. And yet, while development plans

chugged along, "we have never gotten a response from the planning department," Yañez says. "Never, ever."

Yañez and others are banking on the fact that in the past two years, the political landscape has changed. In

2004, when residents first contacted local environmental organizations looking for help, some didn’t even

know where El Sereno was. This past summer, when the sinkhole, a street realignment, and other issues came

to light, the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy fired off a letter to Gail Goldberg, the city’s new planning

director, and Lemuel Pace, district engineer for the Department of Public Works, charging that a revised

Environmental Impact Report was lawfully required. Tim Grabiel, an attorney with the National Resources

Defense Council’s environmental justice project in L.A., has begun keeping an eye on the proceedings.

"Bottom line, the city needs to comply with the letter and the spirit of the law," he says.

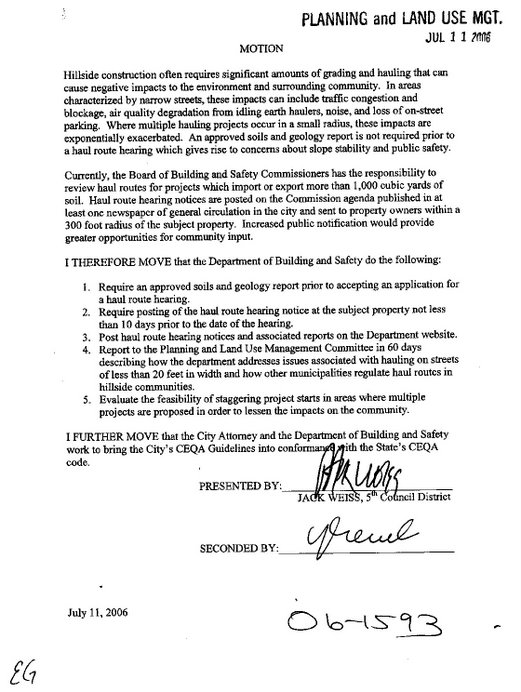

At long last, they just might. Upon taking office last November, El Sereno’s Councilmember José Huizar

inherited the Elephant Hill controversy and at the end of last month, he presented the Planning and Land Use

Management committee with a motion formally directing the Planning Department, the Department of

Building and Safety, and the Bureau of Engineering to finally do what everyone’s been asking them to do – go

back and study the issue, then provide the community with a written report of their findings.

"Huizar represents the political will to do something positive," Yañez says. "He ran on an environmental

platform. This really indicates he’s making good on his promise to protect our hillsides and protect the

environment and engage the city in good development."

Huizar, a former land use attorney who calls himself "an activist in a suit," pronounced himself unhappy with

the amount of time city departments dragged their feet in responding to his constituents. "But more

importantly, I wanted the transparency and the public discussion that goes with the process," he says.

Huizar’s motion, as much as anything, re-opens the community input process, giving residents an opportunity

to come in and testify before both PLUM and the wider city council. And it’s that voice in shaping their city

that they crave.

Public perception of East L.A. has coalesced around any number of less than charitable adjectives over the

years, but residents find much to like in their multi-generational neighborhoods and their strong sense of

community. "Increased property values might sway some people, but for a lot of people it’s about the greater

good of the community," Garcia says.

"These hillsides define our community and they have for a long time, just like the ocean does for communities

closer to the beach." Yañez says. "That’s what’s at stake."

No comments:

Post a Comment