City Beat Article

Victory on the HillElephant Hill residents win a new environmental review of planned development~ By MINDY FARABEE ~

Elva Yañez isn’t quite ready to call it divine intervention, but the timing, she says, is interesting. “Everything started to turn around on Good Friday, 2006,” she notes.

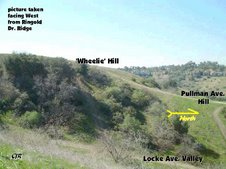

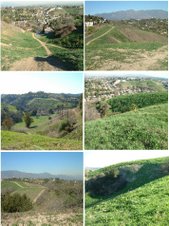

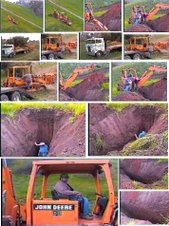

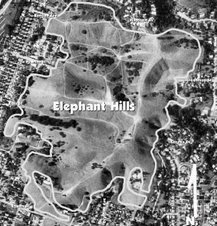

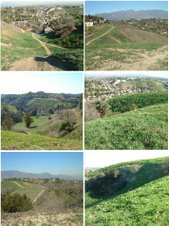

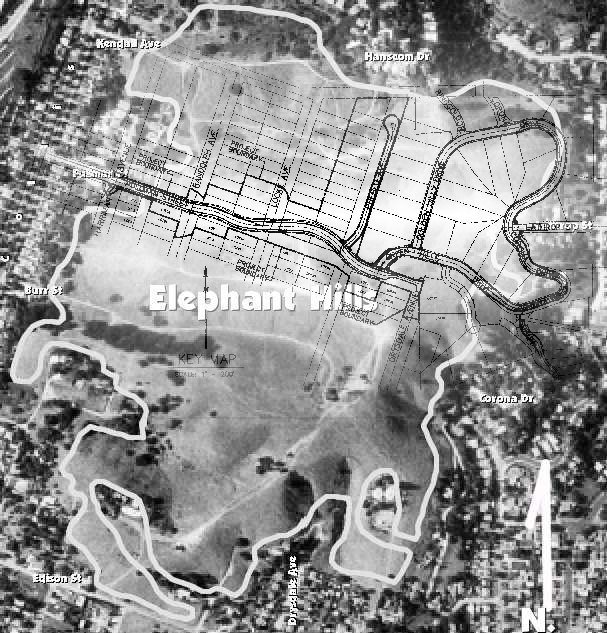

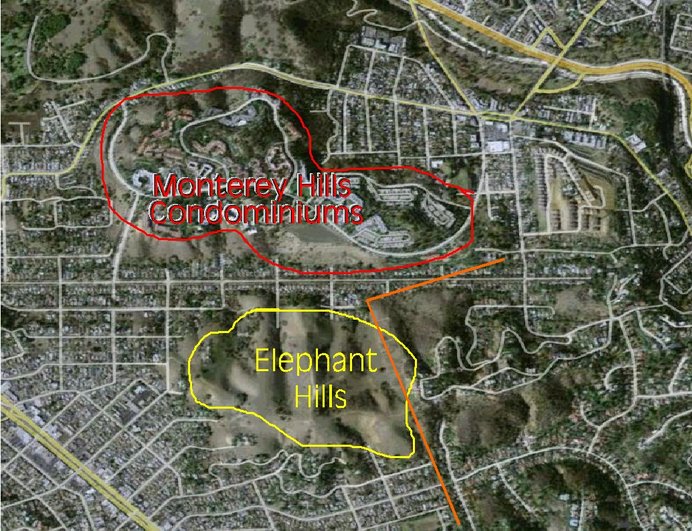

It was that day last April when a backhoe plowing through Elephant Hill – a rare open parcel of 110 undeveloped acres located in the densely packed northeast Los Angeles community of El Sereno – stumbled badly on a subterranean water table and slipped into a sinkhole. It reportedly took two cranes to pry it out, and, while it sat stewing in its own juices, Yañez, a nearby resident and executive director of the Audubon Center in Highland Park, quickly snapped a photo of the mired equipment and began circulating it as tangible proof of what local residents had been saying for 14 years – that this is an inappropriate place to build 24 luxury homes.

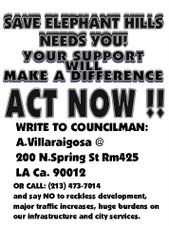

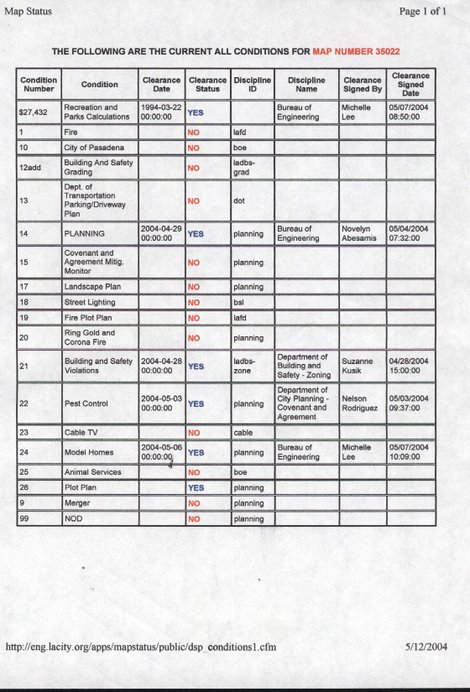

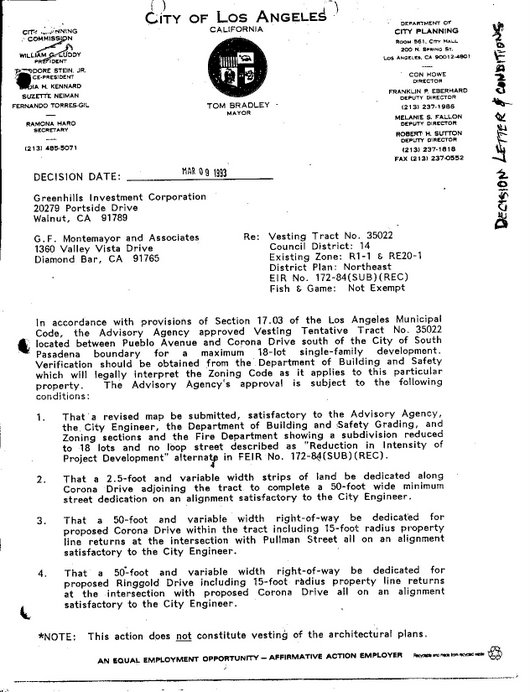

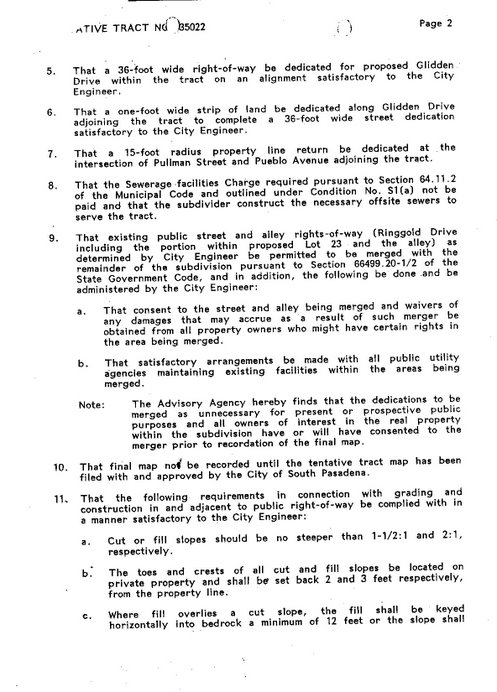

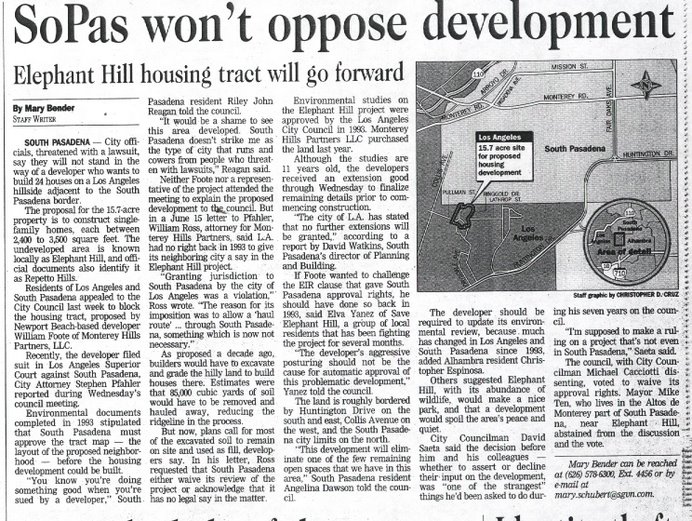

Residents have been fighting the proposed development since the 1990s, concerned about things like congestion and soil instability, and they claim it was originally approved under a flawed, and now outdated, 1993 environmental impact report (EIR). It took 14 years for city hall to concede the residents had a point, but, on June 20, the Los Angeles city council voted to require Monterey Hills Investors to conduct a supplemental EIR. That’s more than one small victory for one isolated group of homeowners trying to preserve a little peace and quiet, advocates say. It’s a historic move, bringing new oversight to one of the poorest and most poorly built-out parts of town, while activists across L.A. hail it as evidence that city government is at last reconsidering its notoriously pro-developer stance.

“It’s a watershed moment,” says Tim Grabiel, an attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), which, along with the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy (SMMC), bolstered El Sereno’s grassroots movement with legal assistance and institutional backing. “In the past, it wouldn’t have happened. Hopefully, it will be a stepping stone toward a more environmentally friendly city.”

According to councilmember Huizar, whose 14th District is home to Elephant Hill, that’s exactly what’s going on. “Today’s city council is one of the greenest, most environmentally sensitive councils in quite some time,” says Huizar, adding that he and his colleagues are turning their sights not only to EIR issues, but also more environmentally sound construction practices and greener philosophies for future land-use patterns. And the dogged persistence of El Sereno residents has affected their thinking.

“When you have a community that’s so united, so single-minded, there must be something to it,” says Casey Reagan, a 45-year El Sereno resident who has spent the past few years walking door to door to organize local opposition. “Even if you think we’re a bunch of loons, just listen to us.”

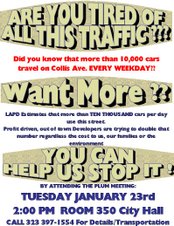

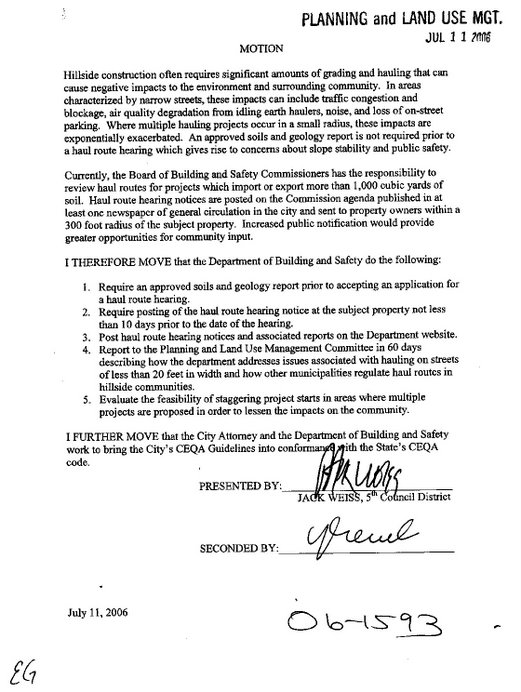

To do that, however, the city had to fight the urge to listen to itself. Earlier this year, Councilmember Huizar introduced a motion in the Planning and Land Use Management Committee (PLUM), asking pertinent city departments to conduct a thorough study determining whether a supplemental EIR was needed. Joined by a wary city attorney’s office, the cautious conclusion was “no.” Huizar pushed to do it anyway. “In this case, I kinda have to go with my conscience,” he said before introducing the motion on the council floor.

Activists are applauding his leadership. A relatively recent addition to city hall, Huizar in no small part owes his job to environmentalists like Yañez who exacted from their would-be councilmember promises to carefully monitor development throughout northeast L.A., especially in its iconic hillsides. Around 10,000 people have been shoehorned into each of its roughly 23 square miles amid a lot of haphazardly planned infrastructure, which suffers from a shortage of green space and parks. Advocacy organizations say children in the area carry the city’s highest rates of obesity. “There’s a running joke that to be able to find green space [in northeast Los Angeles], you have to be buried in Evergreen Cemetery,” says Grabiel.

Connecting those kinds of dots has given rise to a burgeoning ecological awareness with strong social-justice overtones, and the fight over Elephant Hill serves as a rallying cry. That has led to a rethinking of policy decisions, including an interim control ordinance to slow down development in its hillsides, and the SMMC’s formation of an official northeast open space acquisition plan. Huizar’s now putting together a similar task force to study El Sereno specifically, as well as a forum to educate residents about state laws regulating development. In light of geological instabilities – the kind that result in sinkholes and possible liquefaction – which critics charge weren’t properly assessed in initial environmental reviews, residents here are arguing for a citywide moratorium on the current policy of allowing developers to conduct their own EIRs. Councilmember Ed Reyes, meanwhile, has pledged a soon-to-be-introduced motion refining how the city looks at the cumulative impact of ever-increasing construction.

“Elephant Hill was always a catalyst for something bigger, because it was so egregious,” says Yañez. “The city gave them an inch, and they took nine acres.”

That may have proved their undoing. In 2004, when the clock almost ran out on Elephant Hill’s EIR, Monterey Hills Partners, the property’s previous developer, sued the cities of Los Angeles and Pasadena in order to complete approval of its project, thereby slamming the door on a last opportunity to stop the construction. At the time, now-mayor Antonio Villaraigosa represented the district, and he and Reyes, a fellow Eastsider, were the only two councilmembers willing to buck the prevailing wisdom and stand with the community. In the intervening three years, however, expanded tract maps began to surface, showing that approximately 22 additional adjoining lots had been purchased. Under the California Environmental Quality Act, it wouldn’t be legal for an approved project to just add on later without further review, as the cumulative impact of a given proposal must be acknowledged from its inception. In a spirited back-and-forth between Councilmember Tom LaBonge and developer representative Ben Reznik, future adjacent development was acknowledged, although only to be constructed after moving through a separate approval process. According to SMMC math, that would result in a minimum 600 percent increase in the project’s footprint.

“There is no worse case of piecemealing [a project],” testified Paul Edelman, SMMC deputy director for natural resources and planning. “It’s like dealing drugs in front of the police station.”

Just before the councilmembers voted, eight to two, to require a supplemental review, LaBonge offered the developer one last chance to voluntarily perform it.

No thanks, replied Reznik, who also said that his boss “will have no choice but to go to court.”

Rather than ignite another round of legal strong-arming, residents point out that the involved parties should take note of $400 million in Proposition 84 money that will soon become available for municipalities to purchase urban parks. But, if worse comes to worst, “the city made a sound decision and a legally defensible decision,” says Grabiel.

No comments:

Post a Comment