Mindy Farabee strikes again

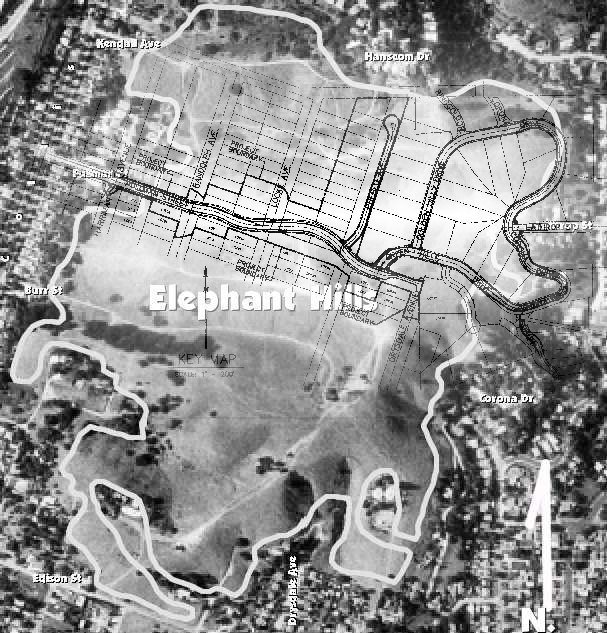

The Battle for Elephant Hill

As the building frenzy seeps into the city’s edges, José Huizar is stumping for smart growth in El Sereno: Development that takes the community into consideration~ By MINDY FARABEE ~

In the great California tradition of naming places after wishful thinking, El Sereno means “the tranquil one.” El Sereno, which lies at the northeast edge of the city, goes back to 1905. But since El Sereno was founded, most of the windows on its stucco’ed bungalows have been barred, much of its breathing room has been clogged by haphazard development, and too many of its kids have joined gangs.

It's not that any one policy actively doomed the place, it’s just that neglecting El Sereno got to be a nasty habit, and that’s maybe nowhere more evident than down at its street level, where bad decisions kept getting made. Just a decade ago, as Caltrans worked to mitigate an extension of the 710 Freeway through tony, neighboring South Pasadena, El Sereno had to sue for the right not to be overrun by a cheaper, clunkier chunk of the roadway. That fight they won, as the two communities collectively killed the project.

Yet even in victory, El Sereno mattered less, as South Pasadena got all the credit. Now, El Sereno is poised to matter more than it has since the last century was young.

Just an hour before a hastily called session of the Board of Public Works — a meeting that would set up a rare city versus city showdown — José Huizar, El Sereno’s City Council voice, lounges on his couch, unrepentant about the brouhaha he’s started.

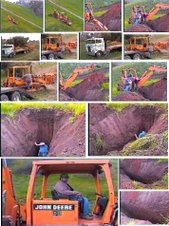

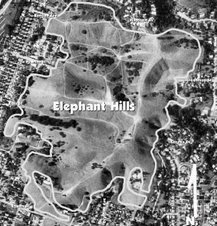

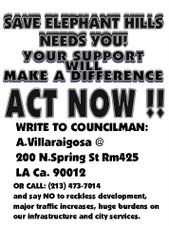

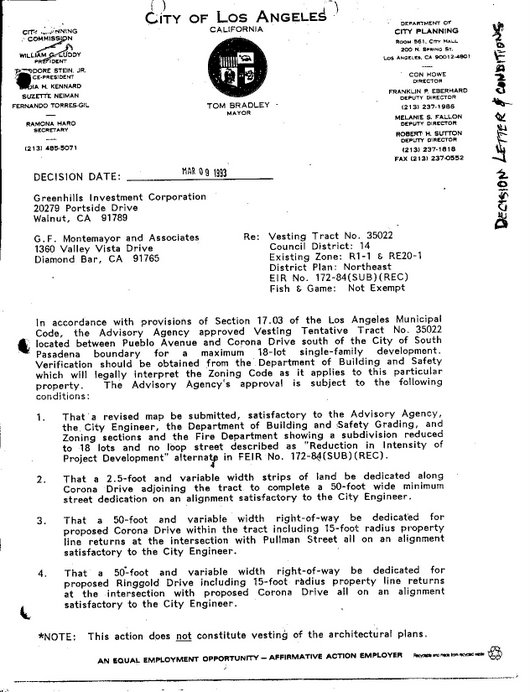

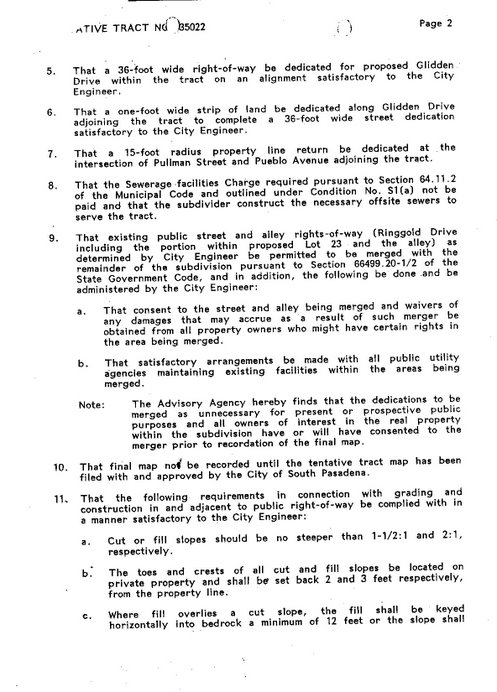

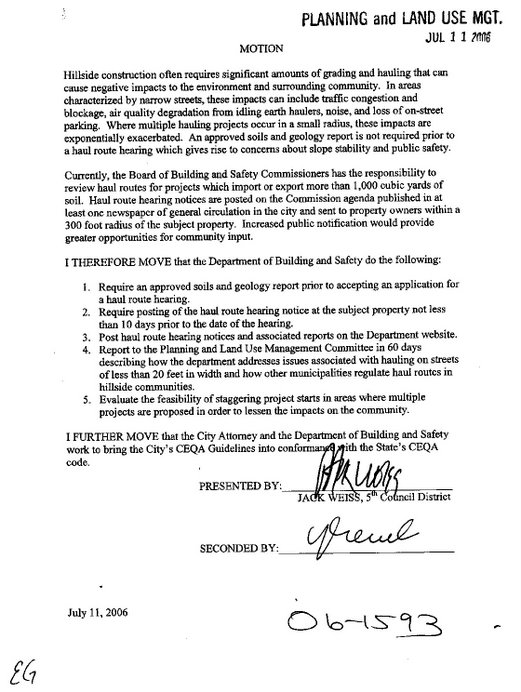

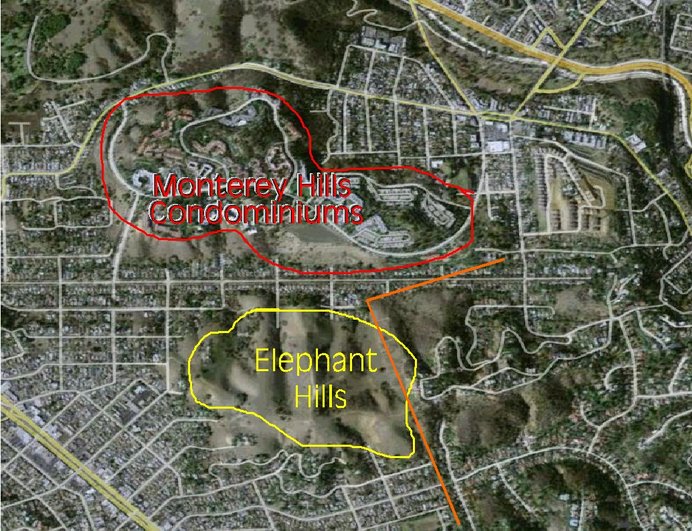

Since 2005, L.A. Councilmember Huizar has represented much of rapidly gentrifying Northeast LA, and as such, this past June, he talked the council into rethinking a 24-home development slated for Elephant Hill, one of El Sereno’s remaining open plots of land. At Huizar’s behest, the Council demanded a supplemental Environmental Impact Report (EIR), potentially derailing the Elephant Hill project.

“As we move forward,” Huizar argues, “you’re seeing the council listening to communities and finding loopholes in how to proceed,” in this case calling for a new EIR, which would cause a major delay.

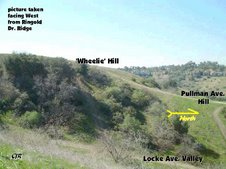

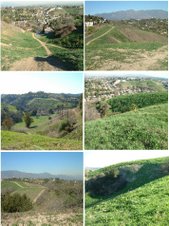

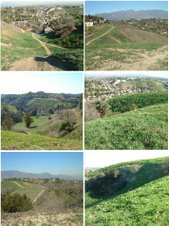

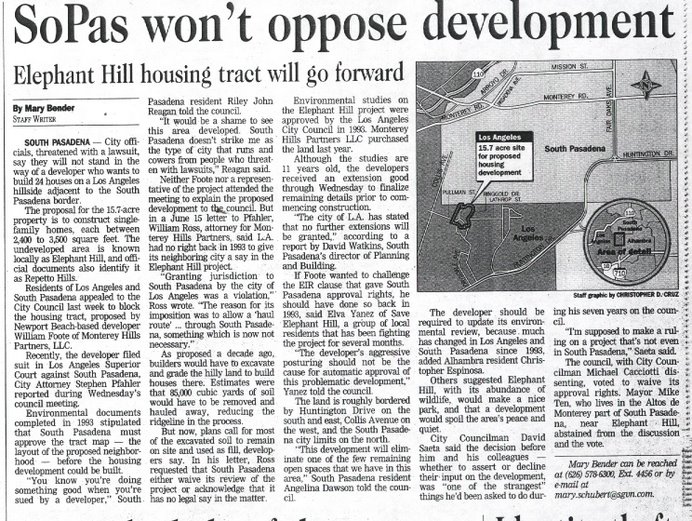

To hear the councilmember tell it, building along 110 acres of gently sloping hillside in El Sereno isn’t just about building along 110 acres of gently sloping hillside in El Sereno, and indeed, almost as soon as the gavel came down in favor of the EIR, an aggressive spin cycle began. Environmental heavyweights the National Resources Defense Council put out a press release calling it a “watershed” moment that could herald a new future for L.A., one that looks at open lands and worries more about community tensions and migrating birds and kids with obesity than property taxes. Council President Eric Garcetti calls the vote “critical for L.A.,” and “worth a fight.” Which is good, because within weeks, as promised, its developer, Monterey Hills Investors, slapped the city with a multi-million-dollar lawsuit and pronounced that something was seriously awry.

“It was quite surprising, to see the council ignore the law,” said developer representative Ben Reznick. “I can only explain it as the city council is politicizing the process. Planning becomes dysfunctional if it’s politicized.”

“Planning in Los Angeles is political period,” insists Huizar. “For someone to call [Elephant Hill] a politicization of the process, that’s because they lost. I could see the arguments on both sides. It comes down to your conscience…what I like is that [my vote] gave people in Northeast L.A. the sense that people in the city are now willing to fight battles for them.”

Serious questions have been raised as to the integrity of the original environmental study used to approve Elephant Hill, as well as whether the project is unlawfully and surreptitiously expanding. In turn, these prompt bigger questions about whether developers have an improperly close relationship with local powers that be. And if that is so, can residents make anyone in City Hall care?

Planning decisions are some of the least understood, least sexy, and most profoundly important decisions to get made at City Hall. They dictate how much smog you inhale, how quickly you get to work, and who your neighbors are. As vice chair of Los Angeles’ Planning and Land-Use Management Committee, Huizar plays an instrumental role in deciding many of them.

Born in Mexico, Huizar grew up in Boyle Heights, one of the Eastside’s cultural and artistic hubs and a longtime seat of its political power. It was there that a strict father kept young Jose out of gangs and an English teacher pointed the burgeoning liberal towards UC Berkeley.

Stints at Princeton and UCLA law school have rounded off some of the edges since then. Mostly. “We used to feel so disenfranchised,” he says, “it was us against them. But now there’s some of us in the them. There’s more room to negotiate as we infiltrate these institutions. Infiltrate,” he stops himself with a laugh. “That was an interesting word choice.”

Los Angeles has fought over redefining itself before. In the late 1980s, slow-growth advocates slammed the brakes on a building frenzy they feared would “Manhattanize” the Southland, a move that momentarily preserved L.A.’s low-density, highway-dependent lifestyle — even as it laid groundwork for the city’s current housing crisis and helped fuel its present transportation nightmare.

But in the past two decades, L.A.’s mushrooming population has narrowed options. As Councilmember Tom LaBonge recently announced on the council floor, “We’re going to build on every available lot in Los Angeles. The question is, ‘How are we going to do it?’”

Los Angeles loves spectacle. But while the rest of the city breathlessly contemplates Grand Avenue and LA Live, and debates the psychological landscape of The Grove, Huizar wants to talk sidewalks. “I want to bring planning down to the community level,” he says. As in pedestrians and public transit and pocket parks. This so-called smart-growth model is not the end of the single-family detached home, but it recognizes that the residents of LA are human, not automotive. It’s not surprising that some of its most vocal champions emanate from the Eastside, where cluttered city blocks are measured in feet, not miles, and rates of car ownership are disproportionately low.

To be clear, Huizar is not promising to save Elephant Hill. As if he could. Until the city articulates a comprehensive new vision of itself, he can only be a monkey-wrench in the works. And he can’t even do this on his own. This summer Huizar wrangled seven others to join him, which as much as anything is what residents here hired him to do.

Weary of decades of provincial backwater politics, Huizar wooed would-be constituents with promises of consensus-building skills and a progressive outlook in tune with other area representatives. Thus, when many savvy NELA voters went to the polls, they were also casting ballots for an Ed Reyes-Garcetti-Huizar triumvirate they hoped would enhance a more powerful, unified regional profile.

Lining up votes for Elephant Hill, then, is significant for articulating who Huizar is. His early leadership was hampered by an uncommonly high staff turnover rate — the stuff of significant local complaints — and the unexpected exit of a deputy who quit to challenge his bid for re-election. Despite having a politician’s ever-present need for popularity, Huizar gives his colleagues credit in the battle for Elephant Hill, calling them one of the most environmentally-minded councils the city has ever had, another possible signal that the ground downtown might be about to shift.

But if it just swings like a late 1980s pendulum, we could all be in trouble. El Sereno needs new housing stock. But in truth, the whole city does. And building anything has become more difficult — not less — over the last few years — at least in the eyes of developers. If communities abuse environmental buzzwords and use blunt political strong-arming to beat back Reznick and his colleagues, the city could make an expensive mess of itself. “If operating differently means ignoring the law, then I think we’re in for some very difficult times,” Reznick warns.

At the fraying El Sereno Community Rec Center a hand-lettered sign hangs on the front gate, reading simply “pool closed.” To one side, a group of adolescents are caged in on the basketball court. But as in much of the area, this isn’t the whole picture.

Close by, there are also rolling hills and historic craftsman homes. There are quiet cul de sacs where the neighbors call out to each other and their children play freely on the streets.What’s still lacking is a piece of paper on file at Spring Street, a Department of Planning memo called a “specific plan” tightly regulating what gets built next, and then after that. Most wealthier and whiter communities got one of those a long time ago. A lot of people in El Sereno know that.

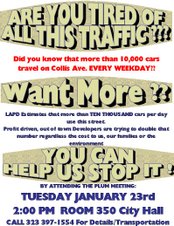

By the time Huizar pulls up across the street 30 minutes late for a planning workshop he’s organized at the Senior Center, the Board of Public Works has taken sides. It’s now a three-way fight: Huizar and his supporters on the Council versus Monterey Hills Investors versus a Public Works Department that’s invested in throwing its bureaucratic weight around: Pulling the rug out from underneath him, the department has issued final building permits for Elephant Hill in direct defiance of the council’s directive. If Huizar can pull together ten votes by September 11, when the council can take the authority from Public Works for the EIR process, he can trump the bureaucrats. If he can’t, El Sereno gets what El Sereno gets.

Mindy Farabee is an L.A.-based freelance writer

Sept. 2007

No comments:

Post a Comment